Tabloid Footprints: The Politics of They Might Be Giants, Part 2

John and John: Troubadours of the Revolutionary Vanguard !?

The second in a two-part series of posts covering class analysis in the songs of They Might Be Giants. Part 1 covered “How Can I Sing Like a Girl?”, “Your Racist Friend”, “Minimum Wage”, and “Snowball in Hell”—check it out here!

Grimace Shakes

“Purple Toupee” is an all-time favorite of mine that lands even harder now that I’ve come to a new understanding of it (fueled by, though not totally in line with, new information gathered from the Don’t Let’s Start podcast that I mentioned last post).

I originally the song was about a gaudy someone who thinks highly of himself that spouts nonsense. Turns out it is that, but it cuts way deeper.

Now I'm very big, I'm a big important man

And the only thing that's different is underneath my hatPurple toupee will show the way when summer brings you down

Purple toupee and gold lamé will turn your brain around

The song’s unreliable narrator is a rich eccentric someone recalling events from the ‘60s (presumably in 1988, when the song was released). His current status as a “big important man” has “[turned his] brain around”—he can’t remember basic facts about defining events of his youth, including…

Civil Rights leaders, events, and causes:

I remember the year I went to camp I heard about some lady named Selma and some blacks

Martin X was mad when they outlawed bell bottoms

Here he mixes up the town of Selma with a woman and thinks that MLK, Jr. and Malcolm X are one person with feelings of minor temperament (“mad”) over trivial matters (pants). Not to mention, he uses the grimace-inducing phrase “and some blacks”. Yikes.

The Cuban Revolution:

I remember the book depository where they crowned the king of Cuba

First off, I swear that I didn't choose to analyze this song simply to have the excuse to write more about Cuba.

Anyway, until I listened to the podcast episode that features this song, I figured that “crown[ing] the king of Cuba” was the narrator describing the popular revolution’s victory as having coronated Fidel Castro, but I didn’t know what to make of the rest.

What I learned—and perhaps you already know this—is that the Texas School Book Depository was the building in which Lee Harvey Oswald was set up during the Kennedy assassination. Instead of the king of Cuba being about Castro, some fans think that it refers to those in the Cuban exile community that were may or may not have been involved in the hit. So, Linnell’s lyrics could be read as wittily poking fun at the failure of those exiles having helped orchestrate a tragedy for nothing: Castro wasn’t scapegoated to the point of inciting a violent coup, and since he wasn’t overthrown, they never got the power they were so hungry for.

… and the Vietnam War:

Chinese people were fighting in the park

We tried to help them fight, no one appreciated that.

This was another line I didn’t get until I read some entries in the ‘interpretations’ section of the TMBG Wiki. It’s killed me ever since.

The more obvious reasons that we know that this is referring to Vietnam is because of (1) the time period of other events in the song and (2) how “no one appreciated” U.S. intervention.

The other reasons bank on us being familiar with the narrator’s topsy-turvy brain by that point: Just when you thought him saying “Selma and some blacks” was bad enough, he assertively misidentifies the Vietnamese as being Chinese. Plus, you know, they were just fighting in a park amongst one another, not being napalmed in the jungle by the West.

While they’re not the only historical facts he mixes up, you may have recognized by this point that there’s a common thread amongst the ones mentioned: They’re dealing with major events that center poor and/or working class people of color.

The narrator, then, is representing the ruling class, whose status allows its members to indulge in foppish fancies like sporting purple toupees and gold lamé without paying mind to any societal injustices past or present, nor any marquee events that shaped the material conditions of the common man. All of these events may have occurred in his youth (“the year [he] went to camp”), yet he has had the privilege of growing up ignorant and unaffected by them since then.

Like the satanic VIPs in Squid Game, this characterization may seem over the top at first, but upon further reflection, it reveals a terrifying and rather accurate stranger-than-fiction truth.

One contributor to the interpretations of "Purple Toupee" on the TMBG Wiki thinks that, aside from clothing, "gold lamé" is a reference to Curtis "Bombs Away" LeMay, whose resumé includes leading hellish bombing campaigns against Japan, Vietnam, and Cuba, as well as being George Wallace's running mate in 1968. Absolutely brilliant.Fremdiĝo estas por riĉuloj

Let’s take a deep breath and get back to the plight of the working man ala “Alienation’s for the Rich”.

The bulk of this song is very on the nose, from its simple country stylings to its lyrics:

I gotta get a job

I got to get some pay

My son’s gotta go to art school

He’s leavin’ in three days

Well I ain’t feelin’ happy

About the state of things in my life

But I’m workin’ to make it better

With a six of Miller High Life

Just drinkin’ and a-drivin’

A-makin’ sure my dues get paid

This is a working class dad who is down on his luck at a bad time. He’s jobless and running out of money at a time when he not only needs to support himself, but his son, as well. To make matters worse, his son is heading to school for a degree that, put lightly, doesn’t guarantee that he won’t end up in the same predicament as the singer down the line. He finds himself drinking his troubles away and hoping that paying his dues will lead to a better future.

The genius of this song comes mainly in two sets of lines:

And the TV is in Esperanto

You know that that’s a bitch

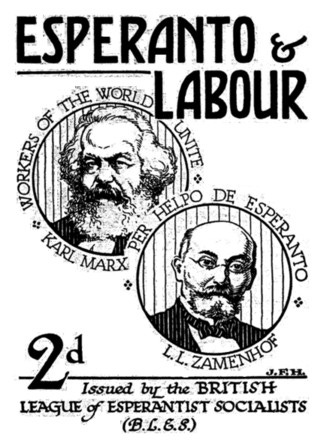

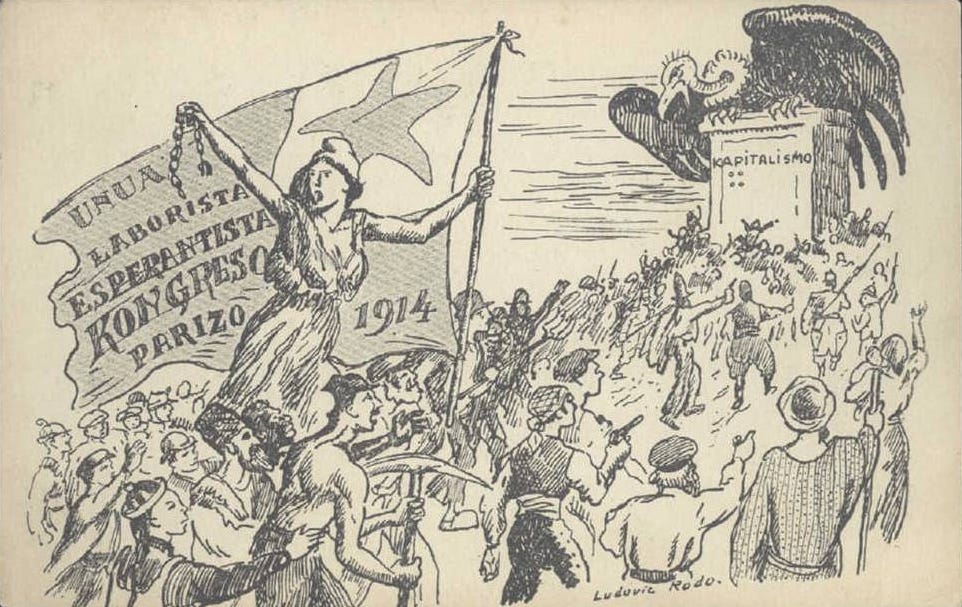

If you’ve never heard of Esperanto, it’s a “universal” language that was created in the 19th century. It was apparently made to be apolitical, though nothing really is.

If one sings of the international working class and adopts “Workers of the world, unite!” as a slogan, one might also believe that a universal language could serve to bolster the organization of mass, international socialist movements. However, it goes without saying that Esperanto, despite being on life support in some Leftist circles today, never caught on.

In the song, our friend is caught in a web of contradictory dissonance: A downtrodden member of the working class like him would never have the bandwidth to touch such an obscure language. Therefore, despite any of its unifying aspirations, the use of Esperanto only alienates him from what’s on the television, presumably unlike, in his timeline, the members of the upper- and middle-class who probably learned it in school.

One may also simply take that line metaphorically: The media is presenting a reality on the television that is so far removed from the working class singer's lived experiences that it may as well be in a foreign language even if that language/content claims to be universal. Either way, it’s a genius choice (and way better than the original line, “the TV’s talking Spanish”).The stanza continues:

But alienation’s for the rich

And I’m feelin’ a-poorer every day

In these lines, the singer makes known his worsening living conditions as exacerbated by the language barrier. He observes that alienation is something that only the rich can afford, and that, as a member of the working class, with each passing day that he’s alienated, the less he is able to cope (thus his “feelin’ a-poorer”).

Remember, “Purple Toupee” speaks to this, as well: Our unreliable bourgeois fop is completely removed from the goings ons of society and that’s fine because he can afford it. But in “Alienation,” our working class comrade doesn’t have the luxury of being unaffected by things out of his control, whether that’s the TV being in Esperanto or the events that the TV is reporting on.

Put another way, it doesn’t matter that the man in gold lamé doesn’t understand important events because he’s insulated from their effects; and it doesn’t matter whether our proletarian drunk driver understands the events or not because they will have an effect on his life whether he likes it or not.

Given Flansburgh’s socialist leanings, perhaps the way the “state of things in [this man’s] life” ties in to the Marxist notion of alienation is intentional. From the wiki on the topic:

The theoretical basis of alienation is that a worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and destiny when deprived of the right to think (conceive) of themselves as the director of their own actions; to determine the character of said actions; to define relationships with other people; and to own those items of value from goods and services, produced by their own labour.

Sounds like this could be our guy. By declaring that he’s spiraling further into despair due to his alienation, he feels that the only thing he can do about it is crack open some cold ones. He no longer feels agency over his life—all he can do is work for his wages and take whatever the world gives him in the meantime.

But also, there may be some hope for him after all. In recognizing his alienated state, he does show some degree of class consciousness. Someone needs to organize this man!

Garbage Time

Having sung of an ignoramus who is blissfully unaware of any harm he causes in “Purple Toupee,” John and John sing of a different type of ruling class figure in “Kiss Me, Son of God.” And it’s a figure that’s all too familiar.

Linnell’s lyrics for this song are very clever, but in contrast to the other songs we’ve looked at, he decides he doesn’t need to be clever about them centering class conflict:

I built a little empire out of some crazy garbage

Called the blood of the exploited working class

Now I laugh and make a fortune

Off the same ones that I tortured

And a world screams, "Kiss me, Son of God"

The song’s subtitle may as well be Socialism 101. Our narrator in this song is a capitalist demagogue. He is someone who has amassing an extreme amount of wealth and power by exploiting his workers for personal gain. .

He’s also a famous, narcissistic public figure that has a very direct, public contempt for those whom he exploits—people who contradictorily worship him as their saviour:

But they've overcome their shyness

Now they're calling me Your Highness

And a world screams, "Kiss me, Son of God"I look like Jesus, so they say

But Mr. Jesus is very far away

Now you're the only one here who can tell me if it's true

That you love me and I love me

I love the lines about Jesus. Even though the lines about looking like Jesus could be interpreted literally in an antichrist sort of way, I take them to be figurative in the sense that he’s describing the unholy degree to which people worship him. Either way, his admission that “Mr. Jesus is very far away” is palpably sleazy. The braggart is completely self aware and satisfied with all of his evils.

Now, at this point, you may be thinking: This dude SCREAMS Donald Trump.

I mean, yeah, for me, too. In fact, I typically think of this video set to the song, which was made when he was running for president in 2016.

Of course, “Kiss Me” was written in 1988. It wasn’t about Trump, and it didn’t foreshadow Trump. Trump is one in a long line of figures in history who have thrived on their cults of personality. He just happens to be most relevant to today’s society (second only, probably, to Elon Musk).

But remembering how big a dumpster fire the Trump administration’s personnel churn was, this line is particularly funny to me with him in mind:

I destroyed a bond of friendship and respect

Between the only people left who'd even look me in the eye

Sure did!

I mean, sort of. God the rest of this year is going to suck.

Where was I? I forgot the point that I was making

So, are the Johns socialists?

I think there’s a strong argument to be made based on the songs covered that if they didn’t identify as such in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s, they probably leaned more towards socialism than any other ideology. They certainly had class consciousness.

Nowadays it’s harder to say. As mentioned in the last post, Flansy outright supported Bernie as recently as 2016, but that was a lifetime ago at this point. I did some quick searches to see if I could catch any hints in recent years, and the only thing that I dug up was that, in the footnotes of their catchy 2020 educational song “We are the Electors”, they write:

Please note this song is FACT-BASED and does not represent They Might Be Giants’ personal views on the Electoral College system. No one is sure how long we can all go along with presidents being elected in spite of losing the popular vote, but right now it seems we should dance with the Constitution that brought us.

Lib? Probably in some ways. Progressive? No doubt in many ways. Social democrat? Probably.

But socialist? Without a turn back to making pointed songs about class relations, I feel like we can close the book on the topic and say They are not.

Hope you enjoyed my dive into these tunes! If there are TMBG songs that I didn’t talk about that make you think they’re commies, sound off in the comments.

Peace,

Greg